Feature

Unveiling Trends, Opportunities, and Challenges Crowdfunding for Health in Indonesia: An Integrative Review

Nuzulul Putri, Ilham Ridlo, Aisyah Rahvy, Leonika Wardhani (The Airlangga Centre for Health Policy Research - ACEHAP) • 14 Des 2023

Background

It has been almost ten years since Indonesia first launched the national health insurance called JKN (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional) in 2014, and as of January 2023 the JKN membership coverage reached 90.3%. In 2023, Indonesia passed a new regulation for health financing, shifting from mandatory spending to budget allocation based on needs and commitment. Low-middle income countries (LMICs), including Indonesia, have benefited from the increasing external aid for their health spending, reaching 2.09% of current health expenditure in 2020 (World Bank, 2023). However, this leads to a fungibility phenomenon where the increase of external aid is followed by a parallel decline in government sources of health spending (Fryatt and Blecher, 2023).

In facing the rise of healthcare costs, high-income countries with a long history of the health system, such as the United States (Blanchette et al., 2022; Igra et al., 2021; N. J. Kenworthy, 2019) and the United Kingdom (Coutrot et al., 2020), have developed crowdfunding mechanisms. Crowdfunding has become popular and can be utilized online using certain platforms, such as GoFundMe, etc. It serves as a method to gather financial support for projects and businesses, allowing fundraisers to accumulate funds from a broad audience through online platforms (Hussain et al., 2023). One specific type of crowdfunding is donation-based crowdfunding, characterized by providing funds without anticipating financial returns.

Even after implementing JKN, Indonesia still deals with out-of-pocket payment or OOP (Couturier et al., 2022). The study also highlighted the average amount of OOP (US$40) and about 61% of it belonged to medicine. Therefore, crowdfunding has the potential to help cover health costs in Indonesia. Indonesia has also been awarded the most generous country based on the World Giving Index 2023 in the last six years. Crowdfunding also has gained much popularity since the COVID-19 pandemic. However, little to no evidence has been examined regarding crowdfunding practices in Indonesia and no prior studies reported challenges and opportunities of health-related crowdfunding. Therefore, this study aimed to identify unmet healthcare needs in Indonesia reflected in the existing healthcare crowdfunding campaigns and analyze the opportunities and challenges of health-related crowdfunding in Indonesia.

Methodology

This is an integrative review with data compiled from existing literatures such as journal articles, online news, and campaigns from KitaBisa with systematic literature search strategy adhering to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses). Our search was conducted using the keywords to identify relevant papers.

((medic*) OR (health)) AND (crowdfunding)

We exclusively included grey literature and news articles from reputable sources and organizations with established reputations for trustworthy reporting to ensure the credibility and reliability of the news articles used. All selected literature was published within the last five years (2019-2023).

Data evaluation was done using Whittemore and Knafl’s Revised Integrative Review Method (Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K., 2005). We focused on documenting the trend of healthcare donation-based crowdfunding in Indonesia then analyzed the unmet health needs reflected and needed to be overcome through crowdfunding in KitaBisa. Moreover, this study also included analysis from online news to further derived information about crowdfunding practices in Indonesia.

The overall data related to crowdfunding practices in Indonesia then categorized into individual, two groups and population health. As stated by Arah (2009), population health is a multidimensional concept which not only sees health as a cumulative individual health metrics but related to broader individual context determining their health status. Hence, we coded a health problem into population health if their risk factors could be owned not only by an individual due to their genetic factors. It is more related to common risk factors that the majority of the population could own and there is public health intervention that can prevent the incidence. We grouped health problems according to the responsible cluster of integrated primary healthcare services (Keputusan Menteri Kesehatan Nomor HK.01.07/MENKES/2015/2023), which consisted of 5 clusters: management, mother and children, adult and elderly, control of infectious disease, and cross-clusters.

We delved into the global healthcare crowdfunding landscape in the final stage to comprehensively understand crowdfunding model profiles. Lesson learned from crowdfunding practices in global context then explored further to synthesize the potentials and challenges of crowdfunding in Indonesia.

Results

28 donation programs depicted in news articles and 646 crowdfunding campaigns from KitaBisa released between 2019-2023 to analyze the profiles of crowdfunding practices in Indonesia. We also reviewed 28 journal articles on health crowdfunding worldwide to comprehensively review the practice of Indonesian crowdfunding.

Reflected unmet healthcare needs in Indonesia in crowdfunding campaigns

After analyzing crowdfunding campaigns in KitaBisa, we found that 646 campaigns were initiated to fulfill health needs of beneficiaries. About 87.62% (n = 566) of total health campaigns were focused on individual health and only about 9.0% were initiated to cover population health funds (Appendix 1). Most population health campaigns targeted injury (60.3%, n = 35), malnutrition (15.5%, n = 9), and infection (8.6%, n = 5). There were also some campaigns that were put in place to help fund clean water installation (5.2%, n = 3) and anemia (3.4%, n = 2).

Meanwhile, congenital disorder (32.5%, n = 184) was ranked first as the most individual health campaign found in KitaBisa, followed by cancer (18,7%, n = 106), tumor (9.7%, n = 55), hydrocephalus (7.2%, n = 41), and chronic kidney diseases (4.9%, n = 28). We identified that most of the funding needs requested in the campaigns for both individual and population health categories are mostly for therapy funding (Appendix 1, Graph 1). The next frequent funding needs requested in most campaigns are indirect costs to access therapy, including travel and living expenses during therapy.

We also calculated the average amount of money donated each time for both campaign categories (Appendix 1). On average, crowdfunding campaigns for individual health put a higher target in collecting funds than campaigns initiated for population health. However, its interquartile range is lower than population health, indicating that the targets among individual health campaigns are less varied. When comparing the donation per donor, donors for individual health are likely ‘more generous’ than those for population health. A donor donated IDR 30,367 for individual health campaigns while only IDR 23,834 for population health.

The actors of crowdfunding practices in Indonesia

We identified that a health crowdfunding actor is not only individual giving through crowdfunding platforms but also through organizational donation programs. We identified that at least 38 donation programs were reported in mass media. The fundraisers for this program-based crowdfunding are organizations from various backgrounds. Private enterprises and NGOs are the most frequent fundraisers. The program-based crowdfunding identified in the news targets more health issues related to population health. Poor health infrastructures and stunting are the two most common issues addressed in this type of crowdfunding. Interestingly, some government bodies such as the Ministry of Health and BPJS Kesehatan (Social Health Insurance Administration Body) also practice crowdfunding, despite the existence of government funding for health programs. Our findings showed that crowdfunding in Indonesia was initiated by institutions from diverse backgrounds, both private and public sectors.

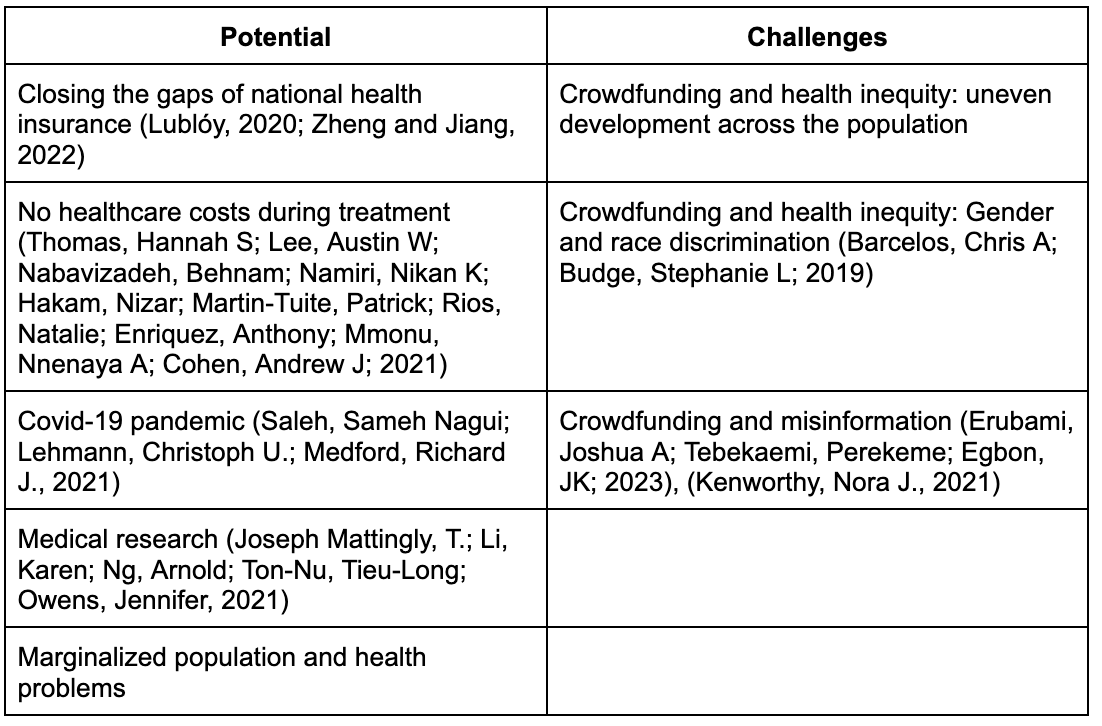

Lessons learned from global crowdfunding practices

28 peer-reviewed journal articles were included and analyzed in this study to document the opportunities and challenges of health crowdfunding in Indonesia (Table 3). Some studies reported that health crowdfunding can potentially narrow the gap and limitation of national health insurance in fulfilling population health needs (Lublóy, 2020; Panjwani and Xiong, 2023; Zheng and Jiang, 2022). In countries that provide health insurance using mixed private-public-funded medical insurance systems, such as the US with their Medicare and Medicaid, crowdfunding is reported to be used to support the increasing costs of medications such as insulin, the inability to pay co-payments, additional or experimental therapies not financed by the health insurance, and rare diseases which were not supported by the insurance (Blanchette et al, 2022; Lublóy, 2020) .

While in countries where the healthcare system is fully supported by tax-based national health insurance, such as the UK, crowdfunding supported the funding of healthcare services uncovered by the National Health System (NHS) so the population can access immediate healthcare services without waiting in long queues (Coutrot et al., 2020). Studies by (Lublóy, 2020; Thomas et al., 2021) explained further that crowdfunding is also used to fund any cost that is not directly expensed for healthcare treatment. Accessing health treatment is also related to the occurrence of non-healthcare costs including transportation, accommodation, living expenses for the dependents, and any other cost which is not funded by the insurance nor the government. However, we were not able to find any article which studied the potential of crowdfunding in filling the gap of Indonesia National Health Insurance (JKN, Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional).

We also found the potential of crowdfunding in the emergency setting such as COVID-19 pandemic (Igra et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021; S. N. Saleh et al., 2021; Snyder et al., 2021). The pandemic had increased the burden of the health system in many countries and triggered the urgency for crowdfunding to address health-related needs during the pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has increased poverty and unemployment, including in Indonesia and further resulted in difficulties in meeting their basic needs and healthcare needs. On the other hand, it increased people’s willingness to help others in Indonesia (Dinata, 2022; Erwan, 2022).

Crowdfunding is also reported being fruitful to support other health issues outside health insurance and COVID-19. Crowdfunding is reported to fund medical research due to the limitation and competitiveness for researchers to get research funding (Aleksina et al., 2019). Crowdfunding also has been used by population in numerous countries to funding non-mainstreaming issues such as the disparities of urban-rural public healthcare system (Ba et al., 2021), and even healthcare needs of marginalized groups such as of LGBTQ+ population (Barcelos & Budge, 2019), advance treatment in other countries (Coutrot et al., 2020), organ transplantation (Pol et al., 2019), substance abuse (Palad & Snyder, 2019; M. Zenone et al., 2020), and abortion (M. A. Zenone & Snyder, 2020). Unfortunately, all of those studies are conducted in non-Indonesia study sites. There were no articles found with Indonesia setting which discussed the utilization of crowdfunding in those health issues.

Table 3. Crowdfunding urgency and crowdfunding implication for health system reported in literature

However, our study also identified the potential harms of crowdfunding practices, derived from the global context. Even though not in Indonesia, crowdfunding is reportedly creating uneven development across groups and sub-population. Crowdfunding is mainly aimed to fulfill unmet health needs but evidence from several countries reported the adverse outcome. Crowdfunding exacerbated disparities between sub-population based on different conditions of the fundraisers. The sub-populations in urban areas are more advantaged than rural ones in accessing social resources to raise crowdfunding campaigns (Ba et al., 2021). There were also some studies which reported that groups with relative socioeconomic privilege disproportionately use crowdfunding to address health related needs (Snyder et al., 2020; Van Duynhoven et al., 2019).

Prior study also reported that higher benefits were found in wealthier regions with higher levels of education, where they were more likely to initiate campaigns and receive more funding compared to people living in areas with lower income and education level (Igra et al., 2021). Campaigns in areas with more medical debt, higher uninsurance rates, and lower incomes of the population had low success rate (N. Kenworthy & Igra, 2022). More successful campaigns are found in regions that are wealthier and healthier, and have more social associations (Lee & Lehdonvirta, 2022).

We then identified some determinants which were related and might influence the success rate of crowdfunding. Technological determinant of health, commercial determinant of health, determinant of health politics are factors which may impact how citizens view health rights and the future of health coverage in conjunction with the rising of crowdfunding for health (N. Kenworthy, 2021; N. J. Kenworthy, 2019). The growth of medical crowdfunding might become the indicator of group-level inequality by reinforcing, or even exacerbating the existing disparities in health access (Panjwani & Xiong, 2021).

These inequity phenomena are also related to the issues of gender and race. Crowdfunding is mostly initiated and used by sub-populations with favorable conditions. Under-represented population is reportedly not benefited much from crowdfunding. People of color (and black women in particular), women, and marginalized race and gender groups are associated with poorer fundraising outcomes (N. J. Kenworthy, 2019; S. Saleh et al., 2020; S. N. Saleh et al., 2020). Moreover, asymmetric knowledge between fundraisers and donors on health problems and poor monitoring of this new health financing source resulted in health misinformation. This misinformation is commonly depicted in the campaign messages that were used to attract donors.

Discussion

Crowdfunding is potentially used to fund health needs that cannot be financed by either the government or the individuals themselves (Lublóy, 2020; Snyder et al., 2020). Although existing research predominantly focuses on high-income countries with established social health insurance schemes, the prevalence of crowdfunding suggests persistent unmet health needs even in such settings (Coutrot et al., 2020; N. Kenworthy & Igra, 2022; S. N. Saleh et al., 2020). There is also potential for its use in Indonesia. However, since limited studies were found in Indonesia as scientific evidence, further analysis is needed to understand how crowdfunding interacts with the established health financing scheme.

Our findings show that congenital disorders are the most frequently addressed health problems funded through crowdfunding. Since this disorder is included among the health problems covered by JKN and ranks first in crowdfunding campaigns analyzed, it could suggest unmet health needs or underutilization of JKN. This is in line with a prior study in Germany that the high number of crowdfunding for certain medical treatment could reflect the unmet needs for available yet non-financed treatment (Lublóy, 2020). Furthermore, since some non-communicable diseases such as congenital disorders and cancers could be intervened to improve the quality of life if detected earlier through proper screening, further consideration should be given to how primary healthcare services have been functioning in Indonesia thus far. Notably, other health problems within the top five in our findings are also preventable issues and their severity could be minimized with early detection.

A crucial focus that should be noted is the allocation of funds requested in the crowdfunding campaigns. Funding for therapy consistently ranks first for both population and individual health. In population health, therapy allocation could indicate that program funding was not yet able to fulfill the preventive action which then led to curative cost in the population (Panjwani & Xiong, 2021). It strengthens the indication of preventive care being delayed, and the population or individual was seeking help only when the condition is severe. Crowdfunding allocation in individual health needs indicates the limitation of National Health Insurance in fulfilling the health care cost since the highest need is for therapy (Blanchette et al., 2022; Lublóy, 2020). Moreover, a qualitative study in Indonesia regarding cancer-related health costs also showed that none of participants were diagnosed at an early stage, and all of them mentioned the insufficiency of their insurance coverage which led to financial toxicity (Pangestu et al., 2024).

The second-ranking funding allocation is related to transportation/accommodation costs, suggesting that despite the availability of services (and free under JKN), people may not necessarily access them due to a lack of financial support for this purpose. Allocating crowdfunding funds for non-therapy indicates the potential of crowdfunding in supporting health financing in societal perspective. Indonesia itself has been struggling with health disparities due to its wide scattered geographic condition (Laksono et al., 2020). The population living in remote areas must travel outside their region to get healthcare services while there is no government program to accommodate this non-healthcare cost (Putri et al., 2021). Our review of news articles shows that poor health infrastructure is the most frequent health problem that is addressed by program-based donation. Different from crowdfunding through online platforms, program-based donations are initiated by an organization by approaching a more well-resourced organization as the donor and target a population.

Crowdfunding can indeed benefit the healthcare sector economically by expanding market participation in healthcare financing, raising awareness of the health conditions of marginalized groups, and demonstrating accountability and social involvement (Igra et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021; S. N. Saleh et al., 2020). However, there is limited scientific evidence about crowdfunding practices in Indonesia, while global research discusses that even crowdfunding is helpful, but there are issues related to social inequality. Studies showed that crowdfunding is often enjoyed by privileged groups with higher levels of education and living in urban areas, highlighting inequality in crowdfunding (Chen et al., 2023; N. Kenworthy, 2021; Van Duynhoven et al., 2019). The subsequent question is how crowdfunding in Indonesia will impact the different socioeconomic status of the population. Currently, among the poor population in Indonesia, a better educated person and living in urban areas reportedly take more benefit utilizing healthcare services under National Health Insurance (Putri et al., 2023).

Furthermore, (Panjwani & Xiong, 2021; Snyder et al., 2020, 2021; M. Zenone et al., 2020) argue that crowdfunding for healthcare financing is considered to pose economic risks such as inefficient prioritization of health development and the emergence of fraud. Considering the new regulation on the absence of minimum health spending in national and local government budgets, a proper mechanism must be implemented to ensure that crowdfunding could beneficially impact the health system and not become the bumper of the limited health budget of the government. Since crowdfunding campaigns also lack a clear measure of impact on the wider community (Lee & Lehdonvirta, 2022), this mechanism is also needed to answer issues on the ethical dimensions of managing crowdfunding. Crowdfunding is also viewed not as a solution to minimize injustice in the healthcare system but, instead, may contribute to injustice (Snyder, 2016). Campaigns that mislead donors, disseminate false information, and even endanger those who receive the funds must be ensured not to occur (Snyder & Cohen, 2019).

Conclusion

Crowdfunding for healthcare funding has been widely adopted in various countries. However, research on crowdfunding practices in Indonesia is still limited, leading to inadequate evidence-based policy recommendations on this potential and challenge to overcome unmet health needs in Indonesia. Our study shows that crowdfunding in Indonesia is highly used in Indonesia to finance health issues for individuals covered by JKN, and treatment costs are consistently at the top of the list. The second-ranking allocation for transportation/accommodation highlights financial barriers hindering access to services, even under JKN which leads to questions about National Health Insurance's effectiveness. Moreover, the identified health problems are also preventable diseases, prompting whether there is a delay in preventive measures. Crowdfunding practices raise concerns regarding social inequality, economic risks, and ethical considerations. Although not in Indonesia, worldwide studies indicate that crowdfunding serves privileged groups that seem to benefit more. Further studies are needed to provide evidence-based recommendations regarding strategic mechanisms, transparent oversight, and prevention of fraudulent practices for crowdfunding's role in healthcare financing.

References

Aleksina, A., Akulenka, S., &Lublóy, Á. (2019). Success factors of crowdfunding campaigns in medical research: Perceptions and reality. Drug Discovery Today, 24(7), 1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2019.05.012

Ba, Z., Zhao, Y. (Chris), Song, S., & Zhu, Q. (2021). Understanding the determinants of online medical crowdfunding project success in China. Information Processing & Management, 58(2), 102465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102465

Barcelos, C. A., & Budge, S. L. (2019). Inequalities in Crowdfunding for Transgender Health Care. Transgender Health, 4(1), 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2018.0044

Blanchette, J. E., Tran, M., Grigorian, E. G., Iacob, E., Edelman, L. S., Oser, T. K., & Litchman, M. L. (2022). GoFundMe as a Medical Plan: Ecological Study of Crowdfunding Insulin Success. JMIR Diabetes, 7(2), e33205. https://doi.org/10.2196/33205

Chen, Y., Zhou, S., Jin, W., & Chen, S. (2023). Investigating the determinants of medical crowdfunding performance: A signaling theory perspective. Internet Research, 33(3), 1134–1156. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-09-2021-0652

Couturier, V., Srivastava, S., Hidayat, B., De Allegri, M., (2022). Out-of-Pocket expenditure and patient experience of care under-Indonesia’s national health insurance: A cross-sectional facility-based study in six provinces. Int. J. Health Plann. Manage. 37, 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3543

Coutrot, I. P., Smith, R., & Cornelsen, L. (2020). Is the rise of crowdfunding for medical expenses in the United Kingdom symptomatic of systemic gaps in health and social care? Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 25(3), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819619897949

Dinata, A. A. (2022). ANALISIS FAKTOR – FAKTOR YANG MEMPENGARUHI PERILAKU DONASI MASYARAKAT KOTA DEPOK PADA MASA PANDEMI COVID-19.

Erubami, Joshua A; Tebekaemi, Perekeme; Egbon, JK. (2023). Contribution of Radio Musical Broadcasting to National Development in Nigeria: A Media Practitioners and Audience-Based Survey in Delta State, Nigeria. https://doi.org/10.11114/smc.v11i6.6120

Erwan, C. (2022). Pengaruh Citra Aplikasi Kitabisacom terhadap Minat Donasi Generasi Milenial di Masa Pandemi Covid-19. 6(1).

Fryatt, R.J., Blecher, M., (2023). In with the good, out with the bad – Investment standards for external funding of health? Health Policy OPEN 5, 100104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpopen.2023.100104

Hussain, N., Di Pietro, F., & Rosati, P. (2023). Crowdfunding for Social Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2023.2236637

Igra, M., Kenworthy, N., Luchsinger, C., & Jung, J.-K. (2021). Crowdfunding as a response to COVID-19: Increasing inequities at a time of crisis. Social Science & Medicine, 282, 114105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114105

Joseph Mattingly T 2nd, Li K, Ng A, Ton-Nu TL, Owens J. (2021). Exploring Patient-Reported Costs Related to Hepatitis C on the Medical Crowdfunding Page GoFundMe®. Pharmacoecon Open. Jun;5(2):245-250. doi: 10.1007/s41669-020-00232-9. Epub 2020 Sep 30. PMID: 32997279; PMCID: PMC8160064.

Kenworthy, N. (2021). Like a Grinding Stone: How Crowdfunding Platforms Create, Perpetuate, and Value Health Inequities. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 35(3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12639

Kenworthy, N., &Igra, M. (2022). Medical Crowdfunding and Disparities in Health Care Access in the United States, 2016‒2020. American Journal of Public Health, 112(3), 491–498. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306617

Kenworthy, N. J. (2019). Crowdfunding and global health disparities: An exploratory conceptual and empirical analysis. Globalization and Health, 15(S1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-019-0519-1

Laksono, A. D., Ridlo, I. A., & Ernawaty, E. (2020). DISTRIBUTION ANALYSIS OF DOCTORS IN INDONESIA. Jurnal Administrasi Kesehatan Indonesia, 8(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.20473/jaki.v8i1.2020.29-39

Lee, S., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2022). New digital safety net or just more ‘friendfunding’? Institutional analysis of medical crowdfunding in the United States. Information, Communication & Society, 25(8), 1151–1175. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2020.1850838

Lublóy, Á. (2020). Medical crowdfunding in a healthcare system with universal coverage: An exploratory study. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1672. https://doi.org/10/gmfvg7

Palad, V., & Snyder, J. (2019). “We don’t want him worrying about how he will pay to save his life”: Using medical crowdfunding to explore lived experiences with addiction services in Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy, 65, 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.12.016

Pangestu, S., Harjanti, E.P., Pertiwi, I.H., Rencz, F., Nurdiyanto, F.A., (2024). Financial Toxicity Experiences of Patients With Cancer in Indonesia: An Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis. Value Health Reg. Issues 41, 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vhri.2023.11.007

Panjwani, A., Xiong, H., (2023). The causes and consequences of medical crowdfunding. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 205, 648–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2022.11.017

Peng, N., Zhou, X., Niu, B., & Feng, Y. (2021). Predicting Fundraising Performance in Medical Crowdfunding Campaigns Using Machine Learning. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10020143

Pol, S. J., Snyder, J., & Anthony, S. J. (2019). “Tremendous financial burden”: Crowdfunding for organ transplantation costs in Canada. PLOS ONE, 14(12), e0226686. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226686

Putri, N. K., Laksono, A. D., &Rohmah, N. (2023). Predictors of national health insurance membership among the poor with different education levels in Indonesia. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 373. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15292-9

Putri, N. K., Wulandari, R. D., Syahansyah, R. J., &Grépin, K. A. (2021). Determinants of out-of-district health facility bypassing in East Java, Indonesia. International Health, ihaa104. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihaa104

Ren, J., Raghupathi, V., &Raghupathi, W. (2020). Understanding the Dimensions of Medical Crowdfunding: A Visual Analytics Approach. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e18813. https://doi.org/10.2196/18813

Saleh, S. N., Ajufo, E., Lehmann, C. U., & Medford, R. J. (2020). A Comparison of Online Medical Crowdfunding in Canada, the UK, and the US. JAMA Network Open, 3(10), e2021684. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21684

Saleh, S. N., Lehmann, C. U., & Medford, R. J. (2021). Early Crowdfunding Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-sectional Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(2), e25429. https://doi.org/10.2196/25429

Saleh, S., Sambakunsi, H., Nyirenda, D., Kumwenda, M., Mortimer, K., &Chinouya, M. (2020). Participant compensation in global health research: A case study. International Health, 12(6), 524–532. https://doi.org/10/gkch5n

Snyder, J., Zenone, M., & Caulfield, T. (2021). Crowdfunding Campaigns and COVID-19 Misinformation. American Journal of Public Health, 111(4), 739–742. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.306121

Snyder, J., Zenone, M., Crooks, V., & Schuurman, N. (2020). What Medical Crowdfunding Campaigns Can Tell Us About Local Health System Gaps and Deficiencies: Exploratory Analysis of British Columbia, Canada. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(5), e16982. https://doi.org/10.2196/16982

Thomas, H. S., Lee, A. W., Nabavizadeh, B., Namiri, N. K., Hakam, N., Martin‐Tuite, P., Rios, N., Enriquez, A., Mmonu, N. A., Cohen, A. J., & Breyer, B. N. (2021). Characterizing online crowdfunding campaigns for patients with kidney cancer. Cancer Medicine, 10(13), 4564–4574. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.3974

Van Duynhoven, A., Lee, A., Michel, R., Snyder, J., Crooks, V., Chow-White, P., & Schuurman, N. (2019). Spatially exploring the intersection of socioeconomic status and Canadian cancer-related medical crowdfunding campaigns. BMJ Open, 9(6), e026365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026365

Whittemore, R., &Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/10/dhbpb8

World Bank, (2023). External health expenditure per capita, PPP (current international $) - Indonesia, Trinidad and Tobago [WWW Document]. World Bank Open Data. URL https://data.worldbank.org (accessed 1.27.24).

World Health Organization. (2020). Global spending on health 2020: Weathering the storm.

Zenone, M. A., & Snyder, J. (2020). Crowdfunding abortion: An exploratory thematic analysis of fundraising for a stigmatized medical procedure. BMC Women’s Health, 20(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-00938-2

Zenone, M., Snyder, J., & Caulfield, T. (2020). Crowdfunding Cannabidiol (CBD) for Cancer: Hype and Misinformation on GoFundMe. American Journal of Public Health, 110(S3), S294–S299. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305768

.png)