Feature

A Scoping Review on Interventions to Reduce the Workload of Healthcare Workers in Primary Health Care of Low- and Middle- Income Countries

T.I. Armina Padmasawitri, Bhekti Pratiwi, Irianti Bahana, Cindra Tri Yuniar, Nadia Hanum, Zulfan Zazuli (Department of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmacy, Institut Teknologi Bandung) • 14 Des 2023

Introduction

Evidence suggests that primary health care has contributed to improved access to healthcare and strengthened health system, all at a relatively low cost.! Furthermore, robust primary health care is crucial to achieving Universal Health Coverage (UHC) since most essential care could potentially be delivered through primary health care. However, particularly in Low-and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs), primary health care is tasked with abundant and challenging roles, ranging from delivering public health measures to curative services. Coupled with the limited size of primary health care workforce, the abundant tasks could result in a heavy workload for healthcare workers. This situation may have dire consequences such as dissatisfaction with work and burnouts that eventually will affect the quality of care.

Various interventions have been suggested to manage or reduce the workload in primary health care, such as through building an effective teamwork. Suggestions have been made to involve more types of health professionals in a multidisciplinary primary health care team. Having an efficient multidisciplinary team in primary health care allows collective competence to tackle complex health issues with various determinants, while also distributing the workload among the team members. A review performed by Scottish Health Technologies (SHT) Group showed that multidisciplinary team in primary health care may improve the clinical process, outcome of care delivered, or patients’ satisfaction. Some countries elevate the multidisciplinary model through implementing interprofessional collaboration. This model transcends mere co-location and parallel or sequential care delivery in the multidisciplinary team. In interprofessional collaboration, healthcare professionals actively collaborate to offer holistic care plans, fulfilling community health goals through continuous and coordinated care. Unfortunately, the evidence of either multidisciplinary or interprofessional collaboration in the primary health care of LMICs is very scarce.

Having a multidisciplinary team in primary health care also allows healthcare workers with higher qualifications, i.e., the medical doctors, to optimize their workload by performing task shifting or expanding the roles of Non-Physician Healthcare Workers (NPHWs). Various studies had shown successful delegation of tasks to NPHWs with proper training and education, mentorship, and support. A recent scoping review found that there was strong evidence on task shifting to nurses that could be associated with increased access to care. A similar but weaker association was also found with task shifting to pharmacists, who were often assigned. with chronic disease management. Studies also recognized that community pharmacies contributed to reducing the workload of primary health care by providing consultation for the management of minor ailment. Unfortunately, the evidence regarding task shifting to pharmacists was mainly concentrated in High-Income Countries (HIC), whereas the evidence from LMICs was very limited. Evidence on task shifting to NPHWs other than nurses, such as midwife, in the LMICs setting was also limited.

Task-shifting can also be expanded to community health workers (CHWs), i.e., healthcare providers who are delivering health services for their community and has lower levels of education and training than professional health care workers such as doctors and nurses. CHWs, with proper training and support, have been shown to have great importance in filling the gap caused by the shortage of professional healthcare workers. CHWs could potentially take over a substantial workload of healthcare professionals in primary health care, especially in providing health education and information, disease screening, and even prescriptive interventions (such as providing personal nutritional plan).

Discussions have explored leveraging informal healthcare providers to take the role of CHWs and deliver essential healthcare interventions. One study identified informal healthcare providers as: informally trained (though apprenticeship, workshops, seminars) providers, receiving out-of-pocket payments, lacking formal registration (operating outside the governmental or organizational oversight), and having no self-regulating professional associations. Though lacking in structure and quality standards, informal healthcare providers utilization is high in LMICs, particularly among the poor population. One of the most often mentioned informal healthcare providers were the unregulated (unlicensed) drug vendors, who did not have formal training in providing pharmaceutical service. There may be benefits for involving informal healthcare providers to deliver primary health care interventions since they are able to reach the population with low socioeconomic status.

Several systematic and scoping reviews have been performed on the various interventions to manage or reduce the workload of high level health workers in primary health care. However, to our knowledge, there has been limited number of scoping review that collates evidence available on task shifting in a multidisciplinary team , particularly task shifting to NPHWs other than nurse, and involving informal health providers in the primary health care of LMICs. Therefore, this study performed a scoping review aimed to compile and evaluate evidence on the interventions. The review evaluated and summarized information available on multidisciplinary collaboration in primary health care of LMICs, particularly task shifting within the team, and the tools used to ease the task shifting, and the current (or potential) involvement of informal healthcare providers to perform CHWs’ role in delivering essential primary health care interventions. The review also identified facilitators and barriers to the implementation of those interventions.

Methods

A scoping review was performed using standardized methodology and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.

Eligibility Criteria

This review included studies addressing task shifting in a multidisciplinary team , and the involvement of informal healthcare providers in delivering primary health care intervention in LMICs. The included studies could be an expert opinion based on research or field experience, interventional or observational studies, including qualitative studies. The included studies could also be literature, narrative, or a systematic review. The study excluded were studies without any published full paper, studies not written in Bahasa Indonesia nor English, and protocol of future or ongoing studies without results. Studies addressing task shifting from secondary or tertiary health care to primary health care were also excluded since the intervention is outside the scope of this study. There was no year restriction in the screening process.

Search Strategy

The search for relevant studies was performed in the PubMed database. Broad keywords were used in the search, i.e., “Healthcare“Professionals,” “Workers,” “Primary Health Care,” “Developing,” “Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” Boolean Operators were used to make the search more efficient. A systematic review research tool was used, and duplicates were removed using the built-in functionality. A manual search by hand was performed by looking at the references of the studies found or by looking at similar studies found during the literature search. Studies were screened for eligibility based on the title and abstract. Studies that were included based on their title and abstract were further screened using the full text, particularly when there was unclear information. The screening was performed by a primary reviewer (TIAP) and confirmed by at least one of the other authors (BP, IB, CTY, NH, ZZ). If there was a disagreement, a deliberation process was performed involving another reviewer.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data was extracted from the full text of the included studies using a standardized form. The extracted data were the characteristics of the study, the interventions performed, the impact or potential impact of the interventions and the facilitators and barriers of implementing interventions. The extraction was performed using narrative synthesis by at least two reviewers (TLAP, BP, IB, CTY, NH, ZZ).

Result

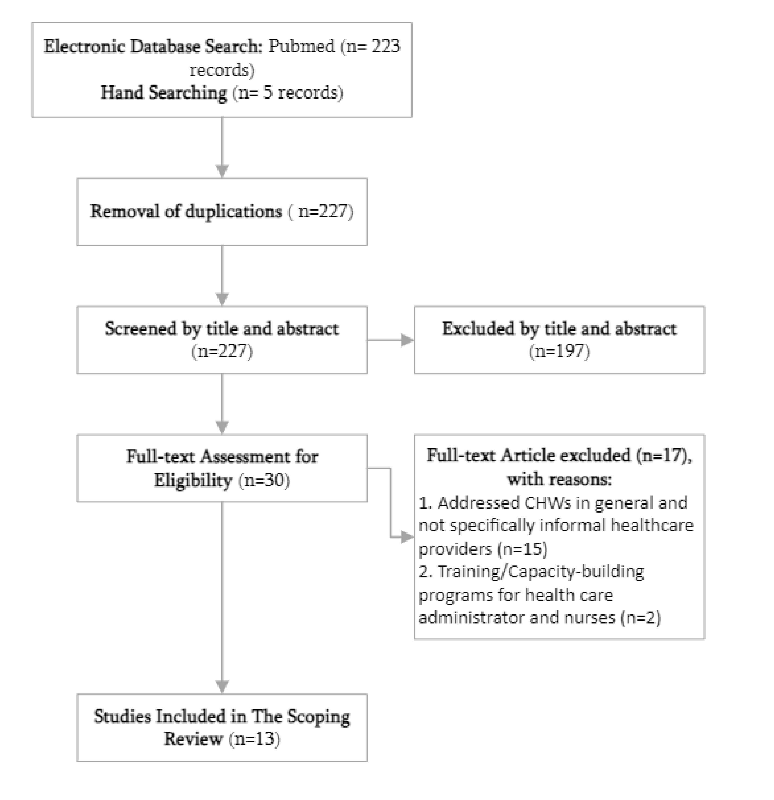

As detailed in Figure 1, the search resulted in 222 hits after removal of duplications. Hand searching references of the studies resulted in 5 additional articles. Out of the 227, 30 articles were included based on the title and abstract screening. The 197 excluded studies were protocol of RCTs (randomized control trials), studies addressing task shifting from secondary-tertiary healthcare to primary healthcare, studies measuring knowledge, attitude, and perception, addressing capacity building not pertaining to workload management or

reduction, studies focusing on improvement of clinical outcome or changes in patients' behavior (without discussing the role of healthcare workers).

Seventeen studies were further eliminated based on full-text screening. The studies were excluded since they did not meet the eligibility criteria. These studies addressed CHWs in general and not specifically informal healthcare providers, and training of healthcare administrators and nurses. The exclusion left 13 studies to be included in the review.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the identification, review, and selection of articles included in the review.

The 13 included studies were mainly performed in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) in Asia, Africa, and South America (Botswana, Brazil, Ethiopia, Kenya, India, Indonesia, Morocco, Nepal, Nigeria, and South Africa). Two studies reviewed articles from both High-Income Countries (HICs) and LMICs. However, the data extracted from the studies were only those pertained to LMICs. The oldest study was published in 2011 and 7 studies (53.8%) were published within the last 5 years (2019-2023). Studies were mainly performed. using qualitative method (7 out of 13, 53.8%) which collected data through questionnaire, in-depth interview, focus group discussion, or combination of those methods. The rest of the studies were descriptive studies (2 out 13, 15.5%), reviews such as systematic or scoping review (3 out of 13, 23%), and econometric (1 out of 13, 7.7%).

Out of the 13 included articles, three cluster of interventions were identified, ie, multidisciplinary team in primary health care setting of LMICs (6 studies), task shifting to the NPHWSs other than nurses (5 studies), 6 and involvement of informal healthcare providers in primary health care (2 studies). Upon further analysis, most of the studies addressing multidisciplinary teams also addressed task shifting within the team and supporting tools for the task shifting. Therefore, we categorized the studies into: (1) task shifting in the multidisciplinary team and supporting tools for the task shifting; (2) involvement of informal healthcare providers in primary health care.

Task shifting in the multidisciplinary team and supporting tools for the task shifting

Two studies mentioned multidisciplinary team approach to manage or reduce the workload in primary health care. A study in Morocco showed that doctors and nurses in the primary health care experienced unmanageable workload. Doctors and nurses had to juggle tasks including administration task, hence they were lacking in time for consultation with patient and often had to multitasked, which could lead to errors. They also found difficulties with incorporating integrated approaches to patient care such as managing physical activity and a healthy lifestyle. The study proposed integrated approaches involving specialist diabetes nurses, dieticians, physiotherapists, and psychologists to allow GPs and nurses to focus on their core tasks. The study also found that the referral system was inefficient and monopolized by one type of healthcare worker. The study suggested that a nurse-led intervention which also allowed nurses to make referrals, could improve the quality of care.

A study from Brazil found evidence regarding the positive impact of expanding a successful primary health care model.In themodel, a comprehensive primary health care was delivered by a family health team comprised of doctors and nurses working from the clinics and the integration and oversight of Community Health Workers (CHWs) who were tasked with monitoring, prevention and health promotion activities. This primary health care model had an impact on the mortality and hospitalization rate for a few diseases or conditions. It also increased the range of services provided and made the services more efficient, while also strengthening health promotion. The details can be found in Table 1.

Five studies mainly discussed task shifting and role expansion to NPHWs other than nurses. Two studies addressed task shifting to mid-level healthcare provider in India, ie., the Rural Medical Assistance (RMA) who received medical training in three years and Indian traditional health medical doctors (allopathic doctors, AYUSH). One of the studies gave clinical vignettes to clinicians and paramedics, then asked them to write a prescription for the case in the vignettes. The prescriptions were graded based on standard clinical guidelines. The RMA scored closely comparable to medical doctors, but allopathic doctors needed more training. Paramedics, mainly consisting of pharmacists and sometimes nurses, scored the lowest across all components. This may be since the paramedics were taking over clinical roles due to the absence of physicians, while never receiving proper clinical care training. Paramedics and allopathic doctors were often found as the only worker providing clinical care in remote populations. In terms of patients’ perception on clinical competence and satisfaction of service, both RMA and allopathic doctors were comparable to medical doctors. Patients’ satisfaction with the performance and perceived competence were the lowest for paramedics. The two studies showed that non-physician clinicians may be able to perform clinical care in the absence of a physician; however, these clinicians must have adequate training, consistent competence, and the patients must also be content and trusting with the care provided by the clinicians.

One study discussed the current role of pharmacist in the primary health care of Indonesia. In Indonesia, task shifting to a community pharmacists (apoteker praktek mandiri) could be performed through two mechanisms. The first one was through allowing community pharmacists to provide care for minor ailments by guiding patients’ self-medication effort. Guided self-medication would allow community health centers (Pusat Kesehatan Masyarakat, or Puskesmas) to manage patients with higher healthcare needs. The second one was through back referral, where patients with stable chronic disease can choose to be referred by secondary health care facilities to obtain their medicine from licensed community pharmacies instead of community health centers. These two interventions showed how community pharmacies were strategically positioned and able to reduce the burden of primary health care. The study mentioned the challenges in the task shifting including lack of recognition and support particularly from the authorities for community pharmacist, ineffective remuneration system such as small dispensing fee that was not directly paid to the pharmacist and late payment for the back referral program, limited size of the workforce, lack of oversight for quality of service, and shortcoming in the pharmacy graduates’ competence.

Another study found an RCT (Randomized Controlled Trials) investigating task shifting to nurses and pharmacists for the management of hypertension. The NPHWs were guided by the WHO cardiovascular (CVD) package that consisted of decision-support tools for the assessment and management of CVD risk through algorithms, lifestyle counselling, drug treatment protocols and referral pathways. The outcome for the consultation with NPHWs guided by the WHO CVD package may be (1) immediate referral to a specialist for patients with high CVD risk; or (2) lifestyle counselling on diet, physical activity, and tobacco cessation; prescription of an antihypertensive medication; and follow-up with a provider. Although marginal (Table 2), the task shifting program group had better blood pressure control than the group receiving standard of care. The study mentioned the enablers for task shifting, ie., continuous educational training and feedback from higher level health professionals, and providing explicit training tools including medication or treatment algorithms. Whereas the barriers for this program were the lack of policy on allowing NPHWs to prescribe medication for common disorders, gap in the referral system for the complicated case, lack of organizational structure to allow NPHWs to provide primary care, and the lack of competence of NPHWs to manage uncomplicated cardiovascular risk, lack of data collection and monitoring to evaluate the performance of the program periodically.

A study performed in Nigeria investigated the role of female CHWsin reducing maternal and childhood mortality and morbidity, and assessing the potential of introducing community midwives. High maternal, newborn, and child mortality rates remains a troubling issue despite existing efforts. CHWs contributed to maternal, newborn, and child health services through providing childhood immunization, antenatal care, and facility-based delivery within the scope of primary health care. However, their effectiveness in delivering these services lacked robust evidence. Meanwhile, the northern part of the country had implemented a “community midwifery" program, introducing a mid-level cadre with more formal education and training than CHWs in maternal, newborn, and child health. Evidence showed that community midwifery increased patient’s access to skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum periods. Based on this finding, the researchers are exploring the feasibility of introducing community midwives into their state's primary healthcare settings, potentially leading to improved maternal and child health outcomes. There were mixed opinions about the CHWs performance on providing maternal and childcare. Underperformance of CHWs were found in severalareas, including record keeping, community mobilization, and timely referral. Some stakeholders believed that bringing local talents educated formally as midwife (community midwife) would be beneficial to increase the number of skilled birth attendants and manage the high number of maternal and child mortality. However, other stakeholders perceived the addition of community midwives would be a duplication of tasks since there were already CHWs working on the health problem. They mentioned that resources were better spent on providing more training to the current CHWs. The study stated that the refusal of community midwives could be a challenge, particularly since CHWs were not considered as skilled birth attendants. Hence, the role of midwives was highly needed, but should be carefully introduced to the region.

Four studies discussed tools to facilitate communication, establishing roles and responsibilities of each healthcare workers, and providing guidance for a multidisciplinary primary healthcare workers team. One review synthesized evidence on decision-support tools that were used to empower NPHWs in conducting certain task and help them adhere to the clinical practice guideline.*5 Unfortunately, the evidence regarding the effectiveness of decision-support tools in maintaining workers adherence on the guideline was very uncertain. There was also no evidence of the resources used for implementing the tools (Table 1). In another study, a Practical Approach to Care Kit (PACK) was implemented in various settings. This kit included decision support tools along with components for training and health system strengthening. The health system strengthening component included translating task-sharing policy to actionable, clear, and consolidated message for all health workers, resulting in a ‘Hymn Sheet’ that explain the roles and responsibilities of each healthcare workers in providing care. The implementation of this comprehensive kit led to reproducible improvements in quality of care for several indicators (prescribing, referral, case detection) particularly for communicable diseases, and had also been linked to fewer and shorter hospitalization.

Two studies discussed the possibility of using mobile health technologies (mHealth). Both studies found that mHealth has the potential to increase connectivity, communication, and collaboration between healthcare workers. mHealth may also empower NPHWSs by enabling them to seek timely support and advice from physicians or specialists to manage patients. Through interaction and consultation with the physicians, NPHWs also had an opportunity to increase competence, and consequently gaining more trust from the patients. Unfortunately, there were some barriers found, i.e., poor network connectivity, no access to electricity, and expensive phone credit recharge. Furthermore, usually these mobile technologies or m-health was built for a single disease or health issue, whereas healthcare workers in primary healthcare may handle several issues at the same time.

Involvement of Informal Healthcare Providers in Primary Health Care

The studies recognized informal healthcare providers asa widerange of practitioners offering healthcare services outside formal training pathways and official licensure structure. Despite their tenuous legitimacy, the informal healthcare providers served a substantial percentage of health needs among poor communities in the LMICs. Although various informal healthcare providers are available, the two studies focused on unlicensed drug vendors. This is in line with the findings in a previous study that unlicensed drug vendors were one of the most utilized informal healthcare providers among lower income communities in LIMICs.

A study from Nepal painted the importance of informal healthcare providers, particularly drug vendors or community pharmacies attended by lay workers. It was found that the community pharmacies were perceived as an accessible provider for hypertension management. The community lay workers in pharmacies who often did not have any formal training were perceived as trustworthy personnel among community members, health workers, and health officials. Thus, they are deemed suitable candidates to deliver hypertension care, such as education and screening. However, further training of non- communicable diseases and steady supply of medication might improve the service provided by them.

Unlicensed drug vendors (drug vendors) managed by untrained personnel, nurses or trained community health workers were also highly sought in rural Nigeria. Drug vendors provided guidance for patients to handle minor ailments or first aid before patients could seek higher degree of care (Table 3). As in the other study, patients perceived drug vendors as the most accessible healthcare facilities due to their strategic geographical location and short waiting- time (relative to the other primary health care providers). The drug vendors often referred their patients to local public health facilities, at the same time patients would also be referred to drug vendors if the necessary medications were unavailable at the health facilities. The study argued that it is possible to formalize the linkage between the drug vendors and formal healthcare providers, such as through mentoring and training programs or community level meetings. However, the quality of drug vendors service varies significantly. Some stakeholders perceived the drug vendors as providing sub-standard care and withholding referrals when needed. This action can lead to a more complicated health issue once the patients eventually seek care in the formal primary health care facilities. The formalized linkage should enable effective oversight of the drug vendors’ quality of service.

Discussion

This scoping review showed that the evidence on task shifting in a multidisciplinary team, and inclusion of informal healthcare providers in the primary health care of LMICs were very limited. The least number of studies were addressing the involvement of informal healthcare providers in PHC. Informal healthcare providers are generally assumed to offer low quality of care since they are not adequately trained and often involved in wasteful and harmful health practices. However, the informal healthcare providers are often the most accessible providers, particularly to the remote or marginalized populations, they may also offer flexibility in payments, and have influences on the people’s health beliefs. Hence, it will be dangerous for the healthcare system to ignore them completely. Building a formal linkage between the informal healthcare providers and PHC isa controversy, but as the studies in this review argued providing a clear regulation for their practice and sufficient trainings and mentorships may be beneficial.

This review found five studies on the topic of task shifting to NPHWs other than nurses. Previous reviews also found scarce evidence in task shifting to NPHWs in LMICs, particularly to workers other than nurses. It was recognized by the studies in this review that task- shifting could potentially reduce workloads for highly skilled healthcare workers while maintaining a good quality of care. This finding is also backed up by findings of studies performed in HICs which showed that role expansion and task shifting could improve patients’ condition and save cost.

Two studies in the review found that pharmacists were among paramedics that provided low quality of care; however, one study showed that with proper training and guidance tools they were able to provide good quality hypertension care. This shows that some enablers must be put in place to achieve successful task shifting.

All programs or tools developed on task shifting contained an element which clearly explains the roles and responsibilities of all parties involved. Clear division of roles and responsibilities has been shown to be an important enabler for multidisciplinary and interprofessional collaboration. Without this element, task shifting could cause ambiguity of role and unclear boundaries between healthcare professionals.> Eventually, this situation would disturb the continuity of care and may produce low quality of care that can harm the patient.

Inadequate level of competence of NPHWs had been mentioned by the included studies as a barrier for task shifting. Therefore, ensuring that NPHWs has the appropriate competence to receive tasks or getting role expansions is an important enabler.This can be achieved through adequate, continuous, high-quality training. However, this issue can also be addressed at the formal education level, where future NPHWs can be trained with competence and skills necessary for potential task shifting and role expansions. Task shifting policy could also benefit from explicit tools such as clinical decision guidance, monitoring, and feedback from healthcare workers with higher competence, and a clear referral system. It has been recognized that the use of clinical guidelines promotes evidence-based clinical decision-making; hence, promoting a safe and high-quality care.

Another facilitator for task shifting is the recognition and acceptance of the role of NPHWs. Part of the recognition is adequate remuneration. Choice of payment can affect the motivation of NPHWs; however, it can also be a source of conflict, especially when remuneration is still in the form of fee for service payment.

It is a consensus that a multidisciplinary and interprofessional collaboration approach could result in a more effective service delivery. Task sharing, and collective competence in an interprofessional collaboration of healthcare workers will allow them to deliver a comprehensive, continuous, high-quality care while also distributing workload among the team members. However, this topic is not very well studied in the primary health care of LMICs. Multidisciplinary approach and interprofessional collaboration may be more studied in secondary and tertiary care settings. This situation could be caused by the general shortage of competent healthcare workers in primary health care. As an example, in Indonesia, pharmacists exist in only half of the community health center to provide primary care. Thus, multidisciplinary team approach may be hindered by the unavailability of the health care professionals to fulfill the role. Furthermore, there are known barriers to collaboration among healthcare workers that might still be prevalent in LMICs such as perception of hierarchy among healthcare professionals and unappreciative of other professionals’ contributions towards patient care, lacking of interprofessional training and education, and organizational issue such as inefficient data-sharing and communication platform.

This review managed to find numerous studies testing the effectiveness of tools to help task shifting within a multidisciplinary team in primary health care. The use of mHealth, including mHealth with decision support tools, had been shown tobe useful to some degree. The appeal of this technology was the widespread use of mobile phones, the possibility to engage with patients directly and reduce the need to make visits, and the possibility of timely communication with other team members. An important highlight from the studies was that technology allowed healthcare workers with lower level of competence to get timely support and advice from the higher-level healthcare workers.

Despite the benefits, evidence showed that mHealth and digital decision support tools can frustrate users when it was badly designed, slow, cumbersome, and constantly malfunctioned. Furthermore, each mHealth intervention usually addressed a single modality (e.g., only for certain disease management), while primary health care workers usually multitasked to tackle various health issues. This evidence highlights the importance of involving users even in the earliest design phase of mHealth and decision support tools. Evidence was scarce in terms of how mHealth can be scaled-up and routinely used. Policy and mechanism regarding incentives or financial support to compensate for the cost paid by users, such as the cost of phone credit recharge, was also not in place yet. Therefore, longitudinal study is highly needed to look at the sustainability, long term impact, and effectiveness of mHealth.

In general, there is a lack of discussion regarding the resources needed to facilitate the interventions addressed in this review. There were also no discussions found regarding how the programs can be financed. Previous study on task shifting also found that there is lacking discussion on how to finance the program, despite evidence from HICs showing that task shifting can be cost effective. Evidence coming from task shifting activities related to top global health priorities, emerging global health issues, and neglected tropical diseases showed that a well-designed task shifting program may even save cost. When enough evidence is present to support task shifting activities, the activity can be included in the UHC scheme. As an example, despite some hurdles, the back referral program to community pharmacies in Indonesia is financed by the national health insurance and predicted to save cost for hospital visit among patients with stable chronic condition. Furthermore, the UHC scheme will reduce tension due to the fee for service payment of the shifted task.

Since the studies were qualitative, the quantitative measure of effect size was very rare. This is understandable since public health interventions are very complex; therefore, it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of these interventions. Capacity building for quantitative research knowledge and skills tailored to the needs of LMICs is highly required to generate more quantitative evidence for public health interventions.

This scoping review managed to expand on previous studies. Asprevious studies have found, although task shifting to various health professionals holds high potential, itis rarely explored in LMICs. This review found that an effective toolkit is often needed to guide the implementation of the task shifting. Decision makers can explore the idea of task shifting to reduce the burden of primary care workers first by mapping the current skill mix and healthcare professional distributions in the primary health care, including those in the private sector such as community pharmacists. Second, decision makers should identify and prioritize tasks that are feasible and need to be shifted. Third, best practices as shown in the included study, such as stakeholder engagement, pilot studies, and toolkit development can be utilized to design a highly efficient task shifting program.

In line with previous studies, we found that informal healthcare providers, particularly unlicensed drug vendors, are often the first choice for low-income communities to obtain healthcare services. The harmful nature of their practice due to limited legitimacy may hinder patients from achieving good health. However, this study found that there is a possibility of aligning their practice with public health goals by formalizing ties through activities such as mentorship, training, or community meetings.

This review has various limitations, including the single database used in the search. However, the search was performed using broad search terms to encompass a wide range of studies. Furthermore, hand searching was performed based on the references of relevant studies. The topic of this review is quite broad. A more focused systematic review on each topic, addressing specific issues such as effectiveness, challenges and facilitators, and resources may give more detailed information. Despite the limitations, this review found the enablers and facilitators often discussed in previous studies.

Conclusion

Although scarce, there was some evidence showing the promising impact of task shifting in a multidisciplinary team, and involving informal healthcare providers in primary health care of LMICs. Lack of competence to provide high quality care was recognized by stakeholders as the main challenge. Hence, adequate education and continuous, high-quality training and supervision are needed. Supporting policies, availability of explicit guidance tools, recognition, and acceptance of the healthcare workers role may also facilitate the interventions. The evidence found in this review is often contextual, qualitative and does not address long-term sustainability, including the resources needed to implement the intervention. Thus, more evidence, particularly multi-settings, quantitative and longitudinal evidence, is highly needed.

References

Kruk ME, Porignon D, Rockers PC, Van Lerberghe W. The contribution of primary care

to health and health systems in low- and middle-income countries: a critical review of

major primary care initiatives. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2010;70(6):904-911.

doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.025

World Health Organization (WHO). Universal Health Coverage. Newsroom. Published

April 1, 2021. hittps://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-

coverage-(uhc)

Hanson K, Brikci N, Erlangga D, et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on

financing primary health care: putting people at the centre. Lancet Glob Health.

2022;10(5):e715-e772. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00005-5

Kinfu Y, Dal Poz MR, Mercer H, Evans DB. The health worker shortage in Africa: are

enough physicians and nurses being trained? Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(3):225-

230. doi:10.2471/blt.08.051599

Leong SL, Teoh SL, Fun WH, Lee SWH. Task shifting in primary care to tackle

healthcare worker shortages: An umbrella review. Eur J] Gen Pract. 2021;27(1):198-210.

doi:10.1080/13814788.2021.1954616

MacLean L, Hassmiller S, Shaffer F, Rohrbaugh K, Collier T, Fairman J. Scale, Causes,

and Implications of the Primary Care Nursing Shortage. Annu Rev Public Health.

2014;35(1):443-457. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182508

Mohr DC, Benzer JK, Young GJ. Provider workload and quality of care in primary care

settings: moderating role of relational climate. Med Care. 2013;51(1):108-114.

doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e318277flcb

Pérez-Francisco DH, Duarte-Climents G, del Rosario-Melian JM, Gémez-Salgado J,

Romero-Martin M, Sanchez-Gémez MB. Influence of Workload on Primary Care Nurses

Health and Burnout, Patients’ Safety, and Quality of Care: Integrative Review.

Healthcare. 2020;8(1):12. doi:10.3390/healthcare8010012

Wright T, Mughal F, Babatunde OO, Dikomitis L, Mallen CD, Helliwell T. Burnout

among primary health-care professionals in low- and middle-income countries:

systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2022;100(6):385-401A.

doi:10.2471/BLT.22.288300

Trindade L de L, Pires DEP de. Implications of primary health care models in workloads

of health professionals. Texto Contexto - Enferm. 2013;22:36-42. doi:10.1590/S0104-

07072013000100005

Zajac S, Woods A, Tannenbaum S, Salas E, Holladay CL. Overcoming Challenges to

Teamwork in Healthcare: A Team Effectiveness Framework and Evidence-Based

Guidance. Front Commun. 2021;6. Accessed October 26, 2023.

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.606445

Zijl AL van, Vermeeren B, Koster F, Steijn B. Interprofessional teamwork in primary

care: the effect of functional heterogeneity on performance and the role of leadership. J

Interprof Care. 2021;35(1):10-20. doi:10.1080/13561820.2020.1715357

Group SHT. An evidence review on multidisciplinary team support in primary care.

Scottish Health Technologies Group. Published April 13, 2023. Accessed October 26,

2023. https://shtg.scot/our-advice/an-evidence-review-on-multidisciplinary-team-

support-in-primary-care/

Wranik WD, Price 5, Haydt SM, Edwards J, Hatfield K, Weir J, Doria N. Implications of

interprofessional primary care team characteristics for health services and patient health

outcomes: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. Health Policy. 2019;123(6): 550-

563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j-healthpol.2019.03.015

Goodyear-Smith F, Bazemore A, Coffman M, et al. Primary Care Research Priorities in

Low-and Middle-Income Countries. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(1):31-35.

doi:10.1370/afm.2329

Chauhan V, Dumka N, Hannah E, Ahmed T, Kotwal A. Mid-level health providers

(MLHPs) in delivering and improving access to primary health care services — a

narrative review. Dialogues Health. 2023;3:100146. doi:10.1016/j.dialog.2023.100146

Evans C, Pearce R, Greaves S, Blake H. Advanced Clinical Practitioners in Primary Care

in the UK: A Qualitative Study of Workforce Transformation. Int ] Environ Res Public

Health. 2020;17(12):4500. doi:10.3390/ijerph17124500

Moola S, Bhaumik S, Nambiar D. Mid-level health providers for primary healthcare: a

rapid evidence synthesis. Published online May 10, 2021.

doi:10.12688/f1000research.24279.2

World Health Organization (WHO). What do we know about community health workers? A

systematic review of existing reviews. WHO; 2021. ISBN 978-92-4-151202-2

Muia D, Kamau A, Kibe L. Community Health Workers Volunteerism and Task-

Shifting: Lessons from Malaria Control and Prevention Implementation Research in

Malindi, Kenya. Am J Sociol Res. 2019;9(1):1-8.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Guideline on Health Policy and System Support

to Optimize Community Health Worker Programmes. WHO; 2018. Liscence: CC BY-NC-SA

3.0 IGO

Perry HB, Zulliger R, Rogers MM. Community Health Workers in Low-, Middle-, and

High-Income Countries: An Overview of Their History, Recent Evolution, and Current

Effectiveness. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35(1):399-421. doi:10.1146/annurev-

publhealth-032013-182354

Sudhinaraset M, Ingram M, Lofthouse HK, Montagu D. What Is the Role of Informal

Healthcare Providers in Developing Countries? A Systematic Review. PLOS ONE.

2013;8(2):e54978. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054978

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the

conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119. doi:10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Tan J, Xu H, Fan Q, et al. Hypertension Care Coordination and Feasibility of Involving

Female Community Health Volunteers in Hypertension Management in Kavre District,

Nepal: A Qualitative Study. Glob Heart. 2020;15(1):73. doi:10.5334/gh.872

Okereke E, Ishaku SM, Unumeri G, Mohammed B, Ahonsi B. Reducing maternal and

newborn mortality in Nigeria-a qualitative study of stakeholders’ perceptions about the

performance of community health workers and the introduction of community

midwifery at primary healthcare level. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):102.

doi:10.1186/s12960-019-0430-0

Sieverding M, Beyeler N. Integrating informal providers into a people-centered health

systems approach: qualitative evidence from local health systems in rural Nigeria. BMC

Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):526. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1780-0

Dankoly US, Vissers D, El Mostafa SB, et al. Perceived barriers, benefits, facilitators, and

attitudes of health professionals towards type 2 diabetes management in Oujda,

Morocco: a qualitative focus group study. Int J] Equity Health. 2023;22(1):29.

doi:10.1186/s12939-023-01826-5

Hermansyah A, Wulandari L, Kristina SA, Meilianti. S. Primary health care policy and

vision for community pharmacy and pharmacists in Indonesia. Pharm Pract.

2020;18(3):2085. doi:10.18549/PharmPract.2020.3.2085

Rao KD, Stierman E, Bhatnagar A, Gupta G, Gaffar A. As good as physicians: patient

perceptions of physicians and non-physician clinicians in rural primary health centers in

India. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1(3):397-406. doi:10.9745/GHSP-D-13-00085

Ogedegbe G, Gyamfi J, Plange-Rhule J, et al. Task shifting interventions for

cardiovascular risk reduction in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic

review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2014;4(10):e005983.

doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005983

Fry MW, Saidi S, Musa A, Kithyoma V, Kumar P. “Even though I am alone, I feel that

we are many” - An appreciative inquiry study of asynchronous, provider-to-provider

teleconsultations in Turkana, Kenya. PloS One. 2020;15(9):e0238806.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238806

Fairall L, Cornick R, Bateman E. Empowering frontline providers to deliver universal

primary healthcare using the Practical Approach to Care Kit. BMJ. 2018;363:k4451.

doi:10.1136/bmj.k4451

Odendaal WA, Anstey Watkins J, Leon N, et al. Health workers’ perceptions and

experiences of using mHealth technologies to deliver primary healthcare services: a

qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3(3):CD011942.

doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011942.pub2

Agarwal S, Glenton C, Tamrat T, et al. Decision-support tools via mobile devices to

improve quality of care in primary healthcare settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2021;7(7):CD012944. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012944. pub2

Rao KD, Sundararaman T, Bhatnagar A, Gupta G, Kokho P, Jain K. Which doctor for

primary health care? Quality of care and non-physician clinicians in India. Soc Sci Med

1982. 2013;84:30-34. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.018

Mrejen M, Rocha R, Millett C, Hone T. The quality of alternative models of primary

health care and morbidity and mortality in Brazil: a national longitudinal analysis.

Lancet Reg Health — Am. 2021;4. doi:10.1016/.lana.2021.100034

Kumah E. The informal healthcare providers and universal health coverage in low and

middle-income countries. Glob Health. 2022;18(1):45. doi:10.1186/s12992-022-00839-z

Rawlinson C, Carron T, Cohidon C, et al. An Overview of Reviews on Interprofessional

Collaboration in Primary Care: Barriers and Facilitators. Int J Integr Care. 21(2):32.

doi:10.5334/ijic.5589

Moncatar TRT, Nakamura K, Siongco KLL, et al. Interprofessional collaboration and

barriers among health and social workers caring for older adults: a Philippine case

study. Hum Resour Health. 2021;19(1):52. doi:10.1186/s12960-021-00568-1

Orangi 5S, Orangi T, Kabubei KM, Honda A. Understanding factors influencing the use

of clinical guidelines in low-income and middle-income settings: a scoping review. BMJ

Open. 2023;13(6):e070399. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-070399. PMID: 37344115; PMCID:

PMC10314507.

Seidman, G, Atun R. Does task shifting yield cost savings and improve efficiency for

health systems? A systematic review of evidence from low-income and middle-income

countries. Hum Resour Health. 2017; 15(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12960-017-0200-9. PMID:

28407810; PMCID: PMC5390445.

Kenneh H, Fayiah T, DahnB, Skrip LA. Barriers to conducting independent quantitative research in low-income countries: A cross-sectional study of public health graduate

students in Liberia. PLOS ONE. 2023;18(2):e0280917. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0280917

.png)